À Gis

The Brazilian trans woman Gisberta lived as an immigrant in Portugal. After she was brutally murdered, she became an icon for the transgender rights cause. Piece by piece, this documentary offers a delicate portrait of a woman torn apart by an indifferent world.

An improvised tent

A mattress

A fur coat

A scarf

A nightgown

Two pairs of gloves

Two lipsticks

Mascara

Eyeliner

A razor

A little box with two mirrors

A purse with six condoms and six pills inside

The summary of a life; a list of all the items found next to the corpse of Gisberta Salce Júnior. Although ‘next to’ might be a euphemism. The lifeless body of Gisberta was found at the bottom of a pit, a few meters away from a makeshift tent that formed her only and last defense against the outside world. Her body, severely injured, was dragged to this pit by a group of kids after they had spent days throwing rocks and other objects at it. The water collected at the bottom of this pit eventually finished the job. I can only hope Gisberta lost consciousness long before.

Gisberta was murdered because she was a woman. Her existence was impossible, unthinkable for the culture surrounding her, so this culture could not allow her livelihood. Gisberta was murdered for who she was, a fact that with some sense of irony— irony in its primordial meaning, hardly distinguishable from tragedy—can confirm her womanliness. Is there anything more womanlike than being murdered because you are a woman? By killing Gisberta, her culture celebrated its inherent misogyny.

Gisberta wasn’t just any woman. She was a trans woman. And those murdered as trans women are to be commemorated as trans women. Until one day, this no longer has to be the case. Until then, we must keep underscoring this fact: in some circles, the only group of people hated more than women are those who, according to those same circles, actively chose to be one. Most women are, culturally speaking, hated. However, that culture also acknowledges they cannot be blamed since these women cannot help it. But those choosing to be a woman—even with a simple gesture like the tone of a voice or an item of clothing—cannot be forgiven for anything. Even after their death, they will not find mercy. Their right to exist and even their existence itself will be denied. This much is clear from the news fragments of Gisberta’s death in the film. These snippets constantly misgender her. As if the murder of her body wasn’t enough and people wouldn’t be satisfied until not only her but her entire image was destroyed, her image as a biblical error, and one her killers claimed touched them to the core. This may very well have been the case; one never forgives another the freedom one cannot grant themselves.

Because she already ran away. From her birth land, a country where statistically speaking, she most certainly would have died a violent death. Off she went, with a French dance company, like her life would finally transform into the fairytale she had always envisioned it to be. The fairytale she chose for herself when she decided to finally become who she already was. Away from her brother, who claimed to love her but not what she was. And once more, the irony, inseparable from tragedy, of his wife—the sister-in-law, a grown woman—introducing Gisberta to her children as Aunt Gis while not fully understanding what they perfectly get; things are the way they are.

Gisberta’s murder holds an important, symbolic place in Portuguese LGBTQIA+ history, similar to the murder of Ihsane Jarfi in Belgian history—a no pasarán after which society decided to enact new laws. Luckily for us (and for her), this film, this short requiem, does not attempt to convince us of the horror by reenacting Gisberta’s death in horrific detail and length, like Animals early last year deemed necessary. The simple act of reading the police file reporting on the cruelties Gisberta had to endure does enough to express the uselessness of the murder and the loneliness of the victim.

What is left of a life lived in the margins? A recap of items found next to a maimed body? An image painted by a social worker? You, the one everybody always called pretty and funny, now have a bad haircut and are in physical decay because you could not get the medication you needed. You, who ended up on the streets and had to sell your body for virtually no money in order to stay alive long enough only to be killed by the hand of others, also marginalised by the same society. You, whom the statistics that structure the world caught up to and who threaten to reduce you to nothing more than statistics for someone else’s hatred. What is left of you now is your name, Gisberta, your name that from now on will always be correct, this name, Gisberta, in which you can become who you have always been. And what is left, Gisberta, are the pictures this film closes with that capture what we lost when we abandoned you and let you die for our sins, Gisberta.

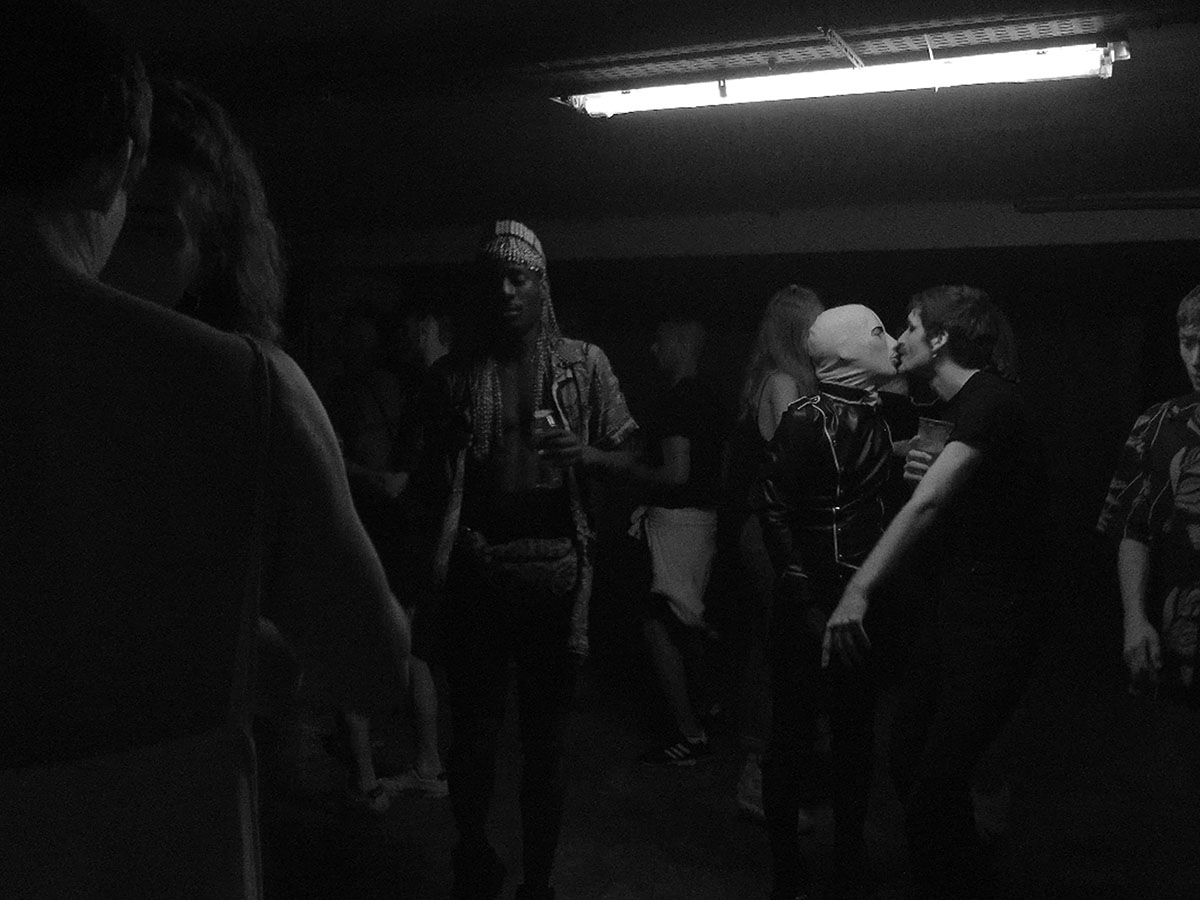

Mexico, October 2011. A mysterious dream gives birth to Cuco, a transgender latex pirate activist. This essayistic film follows their quest to create more recognition for the queer community.